Writers need notebooks. Especially if you’re a first-draft-longhand writer, and/or a planner, you may well buy a notebook for the early stages (or ongoing, side-car stages) of a specific project. But this post is about what I’ll call your general, all-purpose, always-have-it-with-me writer’s notebook.

This isn’t just about stationery, paper or electronic. ‘I work. I have the habit of art’ says Alan Bennet’s fictional W H Auden in The Habit of Art. That the play is set during Auden’s faintly disgusting, dried-up old age is part of the point. What defines an artist’s nature and existence is that they do their art, and keep doing it: a daily, weekly, monthly habit which both shapes and is shaped by the rest of their life. Whether the product that emerges is great art (or even good art) is not what makes an artist: it is the necessity and process of making it.

So shall we call it your habit notebook?

1. What goes into your habit notebook?

overheard voices

a scene: an argument in a cafe, the atmosphere of these woods or this gig, the landscape before you

a metaphor, simile or image that’s prompted by the present moment

a word or phrase that’s new to you

an idea for a story that floats up out of somewhere, something or someone.

a title that floats up out of nowhere and seems to have a story packed inside it.

anything in the current project that demands writing down when you’re nowhere near your main computer or project notebook

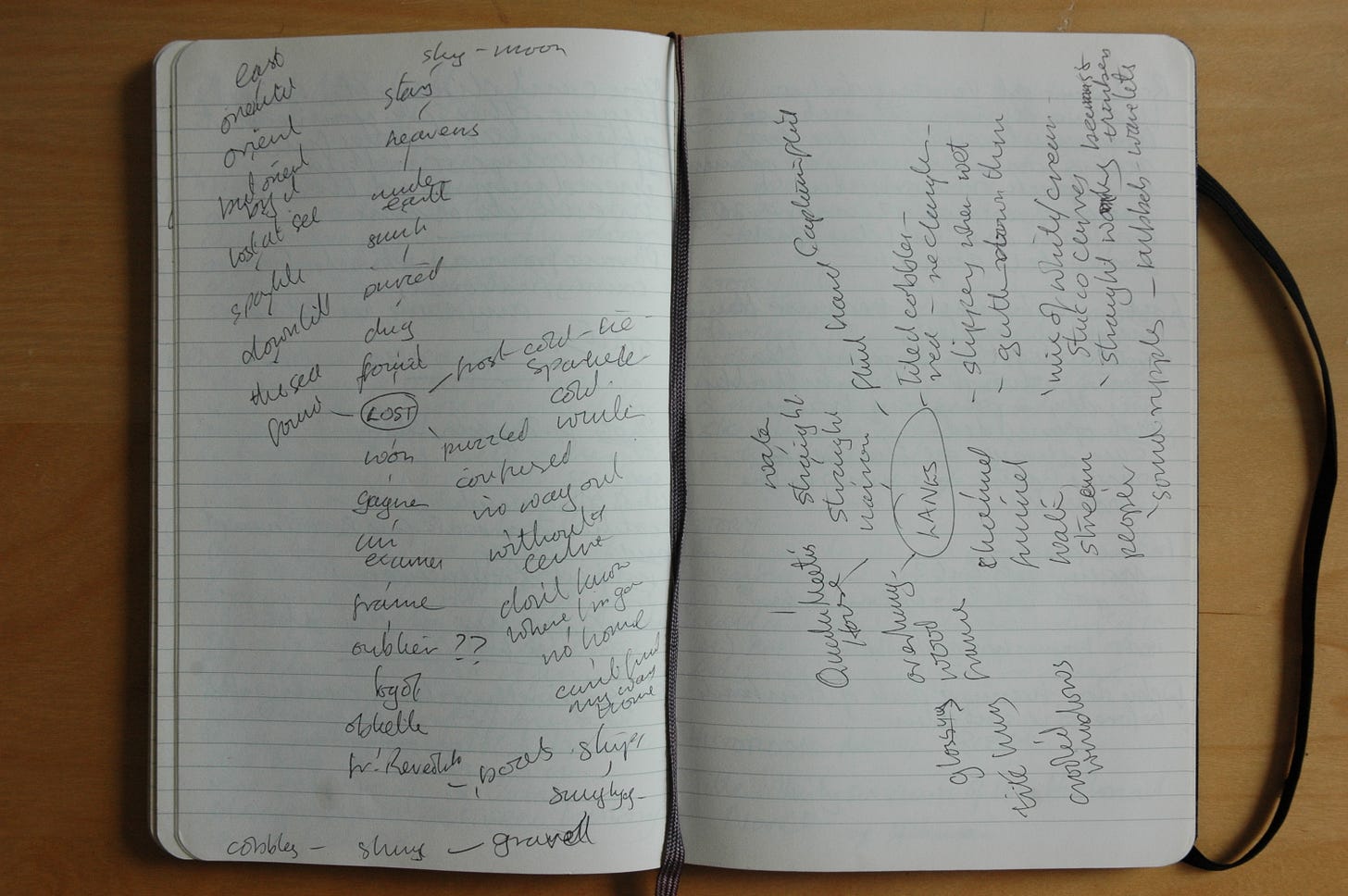

bus-stop exercises: how many smells/colours/shapes can you see? Freewriting, clustering, rhymewells, silly rhymes and bits of poems, re-writing the same sentence a dozen ways

sketches of how a character, setting, building or sketch-map looks in your mind

any other imagining-on-paper (aka ‘planning’) that your current or future project needs: story- or character-arcs; ideas for events, climaxes, motivations or surprises

journal-type thoughts about the current project,

Daily practices such as Dorothea Brande’s ‘appointment to write’ in Becoming A Writer, and Julia Cameron’s ‘morning pages’-type writing, in The Artist’s Way.

probably not an elaborate system of organising and indexing. If each time you grab the notebook to catch an overhearing, you have to analyse the thing in detail for fear of putting it in the wrong section, you’re already editing, shaping or even censoring it, before you can know it properly or explore its potential. You could always keep a rough index-as-you-go at the back.

2. Paper or electrons?

For many, phones have the huge benefit that you always have it with you and a notebook app takes up no extra space in bag or pocket. And taking voice notes can be a godsend when you’re walking, running or driving.

But there’s a strong case for your habit-notebook being a physical one. The batteries don’t run out, you can see the page even in strong sunlight, and if you knock a drink over it you can still just about read the writing. The more significant reason is your pen-in-hand is so much more responsive to the movements of your mind than your thumbs: crossing-out a dealt-with thought, spinning out a mind-map, or circling text to express where it must move to.

And, of course, much of the best creative thinking needs you to be in your head, safe from the eternal tug and dark playground of the online world - and physical notebooks don’t have wifi. What’s more, typing handwritten notes into Scrivener or your main project file is an excellent way to bring them up to the front of your mind again, and review them.

You may find that actually you want both, jotting things down in whatever form comes to hand and periodically rounding them up. If the note turns out to have a use beyond the value of having been written - and one of the key reasons for writing things down is simply to plant the idea more firmly in your memory - you can always review and combine them later. You can even get ‘smart’ notebooks which are both physical and electronic.

3. Don’t stint on your notebook.

For years, I couldn’t bring myself to spend £10 on a Moleskine. Admittedly, a tenner was worth more then, I was skint(er), and in my refusal there was also a whiff of I-don’t-want-to-look-like-I-worship-Bruce-Chatwin. Then I was given one, and discovered the joy of a really good notebook: gorgeously smooth, tough paper you can write on no matter what pen or pencil you have, and erase too; the elastic closure so it doesn’t swallow thing or jam when you stuff it in your bag; the hard cover so you can write on your knee under the table; and the pocket at the back for leaflets, labels and drunken notes on a napkin. (Although, for what it’s worth, these days I mostly buy Leuchtturms.)

But, also, Moleskines are plain and dull, not a beautiful treat that I should fill with no writing that is worthy of it: there was no need to judge or censor what I let onto its pages, and when it was full I could buy another, identical one. So bear in mind that your notebook

should still be a practical, working thing; don’t buy a notebook you can’t bear to besmirch, try things out in, make a mess, scribble all over, and use up;

should not fall apart after a few weeks’ knocking around in your backpack, nor have pages so feeble they tear when you try to erase, scrumple when you scribble a biro to get it working, or bleed ink onto the next page

needs to be small and slim enough to carry around, large enough to write on comfortably - but not so large you need a table to rest on.

if it’s electronic, it needs an interface which takes minimal swiping or clicking before you can make your note,; tracks and shows pages easily; syncs absolutely reliably; and exports pages easily to other programs.

should have the printed feint that suits you. Lines keep your writing reasonably tidy and contained; blank helps you relax into free-form sketches and spider-diagrams but may be less good for keeping chunks of prose readable; squares channel your inner French schoolchild; dots, for some of us, are the perfect compromise.

might have numbered pages so you can log at the front where anything really crucial is.

is, above all, a key tool of the trade. If you’re serious about your craft, then as far as financially possible don’t stint on what it costs to get you the tool that’s right for you in quality and design: paper, binding, shape and size - or, alternatively, screen, interface and perhaps stylus. Your writing needs it, and deserves it.

I practically live in a notebook - have done for years now. Recently I shifted to a two-notebooks system: one general, one for the current project, where I keep together brainstorming, story calendars, name lists, word-count tracking, lists of questions, plans, moon-phases (yes, well...), epiphanies, bibliographies, character sketches, to-dos, the occasional map, and... things. The general one is for everything else. And since I'm a little scatterbrained and I have trouble working on only one thing at a time, the separate notebooks help me to keep my various sheep in their different meadows, at least. All my WIP notebooks are Moleskines, all my general notebooks are Paperblanks - all of them unlined, because lines or grid make me feel... oh, I don't know: cramped, I guess.

There should be a special word for writers' addictions to notebooks!